Ted Sheridan is an architect and artist based in New York City and the Catskills. As an artist, he uses combinations of oxidized and pure metals as a marking medium on paper that is then transformed through immersion and corrosion of the metals. An instrument maker, and musician he has instructed courses on architectural acoustics and the physics of musical instruments at the Parsons School of Design in New York. Sheridan is a partner at Ryall Sheridan Carroll Architects.

Simona David: What drew you to the world of architecture? Where does your passion for design come from?

Ted Sheridan: I have always liked drawing, but making models really got me excited about building bigger things, and making musical instruments got me very tuned into architectural acoustics. Visiting Toronto, Detroit and Chicago when I was a boy had a big influence on me.

SD: You mention musical instruments. Please, elaborate.

TS: When I was a student, I had a professor, Scott Arnold, who is a collector of musical instruments, particularly African instruments. He had an astonishing collection of kalimbas that really intrigued me; I tried to build a similar instrument, and really struggled with it – I was making it based on a visual idea and it barely functioned. I was lucky and met a master instrument maker at the time, Ben Hume, in New York City. I joined his shop as an apprentice and that’s where I had the opportunity to learn the traditions of musical instrument construction and understand the acoustical basis of these beautiful objects. These are forms that people look at and consider to be beautiful – but the way the instruments look is a result of a centuries-long evolution of their shapes and surfaces driven by how they sound.

The architectural process of making drawings, models, and renderings for clients is overwhelmingly a visual exercise; designing musical instruments made me appreciate the potential of thinking aurally, or sonically about architectural design. I have done quite a few installations centered on creating musical spaces with the architectural forms.

SD: Notable recent projects include the Dune house in Long Island and Robert Rauschenberg’s Studio in Manhattan. Talk a little bit about each of these projects.

TS: My office specializes in very high-performance, energy efficient design, and the Dune House is designed to International Passive House standards – one of the most stringent efficiency standards in the world. With a modest set of solar panels on the roof, the energy bills on the house are essentially zero over the course of the year and the interior is extremely stable and comfortable.

We try to weave the efficiency measures into the aesthetics and the detailing of these projects from top to bottom – and we try to let the natural character of the materials really stand out. This house just won an American Institute of Architects award for residential design. Some people describe it as “ship inspired” but for us, any overt symbolism isn’t really the point: what we strive for is a kind of synthesis between the forms and materials and the sustainability measures, so that the efficient design is really embedded in the architecture and not just added onto it.

SD: The European design magazine Dezeen had written about this project at https://www.dezeen.com/2023/03/01/ryall-sheridan-carroll-tree-farmers-house-long-island-home/). How about Rauschenberg’s studio?

TS: The renovation of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in New York City is a particularly special project for me because part of it was restoring the beautiful former chapel that Rauschenberg worked in for decades – often on his hands and knees on the floor doing large scale drawings and prints. The chapel space has amazing lancet windows and perfect light for viewing Rauschenberg’s most challenging visual works: his white paintings. These are paintings that are so subtle that the light in the room needs to be perfect to really appreciate the grain and texture of the brushstrokes. John Cage really admired these paintings that simply cannot be represented in photographs – you need to see the originals in the best possible light. And when they were recently exhibited in the space, they looked fantastic.

SD: This project was featured in ARTFORUM, where you are quoted as saying: “We wanted to make it better for viewing artworks, safer for the artworks, and more comfortable for the occupants.” Full article is available at https://www.artforum.com/columns/ian-volner-assembling-robert-rasuchenbergs-studio-517921/

SD: Architecture shapes our environment, both physical and cultural, in such a significant way – we often associate different styles with different periods of time. Do you ever take the time to ponder about this?

TS: Quite often. The way we conceptualize space in the Western world is a rational, often rigid, and efficient approach – the Roman way of town planning on a grid that definitely had a perspectival concept. Indigenous cultures, particularly non-literate groups don’t do this – they create more circular, softer spaces, more anthropomorphic and actually much richer acoustically.

SD: You have done quite a few projects in the Catskills as well, like for instance The Print House and 1053 Gallery in Fleischmanns. What makes these projects special?

TS: I love the Catskills and it’s really an honor to do projects in Ulster and Delaware counties. There are thousands of interesting houses and buildings in the Catskills that really are part of the living history of the place, and I never get tired of looking at them. The 1053 Gallery is a particularly special project. When Mark Birman, the owner, approached me about renovating it, I could see it right away as a kind of glowing beacon in Fleischmanns that would bring people together for openings and events. He had a real vision for the place and was absolutely committed to making a gallery that would draw people in from the entire region and beyond. When we finished it and the openings were actually happening, people were spilling out onto the street which was fantastic. It has a nice balance of first-rate lighting and display space, with a bit of the “Catskills edge” retained in the rough steel ceiling beams and the raw plywood floor. I like the way old steel looks when it’s corroded – and you can see this in my artwork, so we carefully cleaned the beams while keeping the patina intact.

The Print House grew out of the 1053 Gallery in a way and the two projects now reinforce each other. Joe DeVito, who runs the Print House, knew about the Gallery early on and was a regular visitor. He had the energy and vision to transform what was the Purple Mountain Press into the welcoming space it is now. There is a lot of back and forth between the two spaces which is very satisfying to see. This is a key aspect of successful urban spaces: that their components face each other and define a kind of collective zone where people can be at a destination, and at the same time, see another one nearby. Particularly in the evening or at night, this has an effect where the spaces reinforce each other and make the experience of the Village a special one.

SD: And of course, you designed your studio in the Catskills which you share with your wife painter Amy Masters. How did you pick the location of the studio? What inspired you?

TS: We added the studio to our small house out of necessity because we really couldn’t do artwork in the house. It’s a two-level studio so we can work in the space at the same time quite easily. We decided to attach it to the house so we wouldn’t be discouraged by bad weather and snow which was a good decision. We’re on a north slope and Arkville gets a lot of snow. It’s very efficiently designed with a ceiling angled so we can easily talk to each other while working on different levels and not being distracted by what the other is doing.

SD: Who are your influences? What style are you most fond of?

Working in music and architecture, I’m influenced by spaces that sound good and have a real acoustical character. Architecture is most commonly treated as a visual art, but it actually isn’t that at all. Regardless of the visual concepts an architect might have, the built form is a kind of acoustical or sonic animal – and those aural qualities are usually complete accidents. But it doesn’t have to be that way, and musical instrument makers figured this out centuries ago, they just tended to keep what they knew a secret. Sound is one of the integral aspects of architecture. So, I’m not really interested in particular styles but I appreciate buildings that sound good and are conducive to speaking and listening. There are a few architects who have had real awareness of this – Iannis Xenakis, Giancarlo De Carlo, and Bernhard Leitner, for example. And the entire tradition of the Gothic Cathedrals was a magnificent project in the design of musical spaces – the choral power of Chartres or Nantes in France is beyond description.

Generally, I’m drawn to minimalist design that still expresses how something fits together or stands up. My two partners, Bill Ryall and Niall Carroll, and I don’t use a lot of ornamentation in our work – there are not a lot of traditional details. But we like to emphasize the materials we use in a very “up-front” kind of way and not conceal, blur or erase them. Catskills hemlock, unfinished, and rough sawn happens to be one of our favorite materials. We do pay attention to acoustics, and the highly insulated building envelopes we design make for very quiet and serene interiors. We treat every job as completely new, we get to know the context, understand the client’s character and point of view. We don’t bring a preconceived notion of what any particular project is going to look like. The process will inform that. We have designed a lot of galleries and artist studios and with art, we’re always focused on the quality of the lighting, making sure it’s done right.

SD: What do you find most rewarding, and also most challenging in your work as an architect?

TS: I do like the process of construction and working with clients and contractors who are interested in quality work. But construction is also the most challenging – it can be a real minefield where things go wrong, and everyone has to get together to problem solve. Even the toughest ones work out in the end, but it can be a long road sometimes.

SD: And also as an artist, you do metallic prints. Talk a little bit about the process, and share some of the works you have done recently.

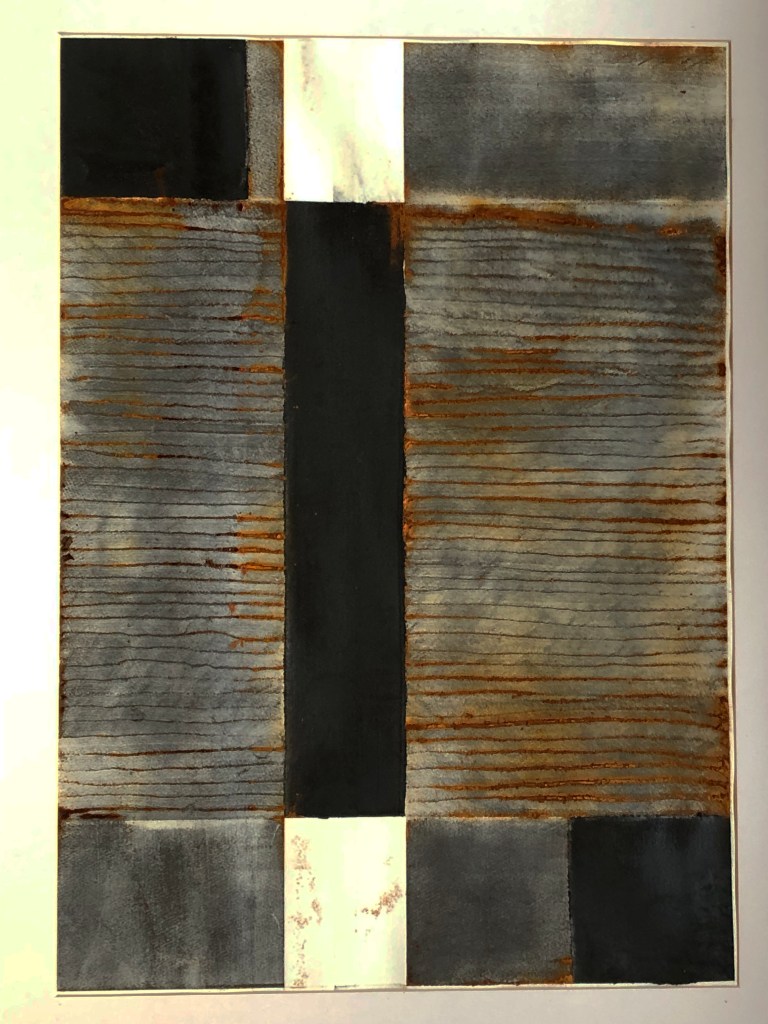

TS: I’ve always been fascinated by how buildings age and wear over time, and have done some large raw steel facades. I started doing metallic prints as a way to use corrosion as a medium, so I work with pure iron powder and grind it into heavy paper or plywood and then soak it to allow the corrosion process to take place. The initial work with the dry powder is somewhat controlled, but once it’s wet or submerged, there is a lot of random action and unpredictability. I like that – it’s an antidote to architectural drawing which is so precise and ultra-determined by nature. I’ve done a series called “Furrows” using a plowing technique with the powder that creates an interesting scrim effect that’s quite unique.

SD: What other media do you work in?

TS: Quite a bit of watercolor that is very loose and abstract – trying to create the same combination of intentionality and chance on the same page.

SD: Are there any other projects you’re working on that you’d like to share?

TS: There are a few houses in the Catskills, and I’ve been lucky to also work on the Weaver Hollow Brewery in Andes, and the Delaware and Ulster Railroad stations in Arkville and Roxbury.

SD: Any upcoming shows?

TS: I am currently working toward a 2024/2025 show – details will be announced soon.

Ted Sheridan is a partner in the architecture firm Ryall Sheridan Carroll Architects, along with William Ryall, FAIA and Niall Carroll, AIA.

You can learn more about their work at https://www.ryallsheridancarroll.com/